To reconstruct Rembrandt’s teaching activity we must also rely on works of art, in addition to written documents and sources, since the records of pupil registration in the St. Luke’s Guild in Amsterdam were destroyed long ago. His pupils were advanced, known as disciples (“discipelen”). They carried out exercises and contributed to finished paintings that Rembrandt could sell as products of his studio. Rembrandt even identifies several such sold works by his disciple Ferdinand Bol in a short note on the back of a drawing.1 And pupils occasionally may have been allowed to sign their own works, although this remains unclear. But the authorship of many other such works may well have been hidden behind a general label of his studio. Over the years it has been possible to ascribe various unsigned studio works with confidence to specific disciples. Of the works that remain anonymous, one of the most tantalizing is surely a large canvas in The Wallace Collection depicting The Centurion Cornelius, last unconvincingly attributed to Willem Drost (fig. 1).2 Its style indicates that it took shape on an easel in the pupil’s atelier around 1653.3 It shows similarities to several other early, Rembrandtesque works that likewise show boldness, bordering on recklessness, in handling. These can be linked to one of the pupils in the studio at the time, Heyman Dullaert, by way of signed works by him in Groningen and Jerusalem. Thus placed, The Centurion Cornelius gives us a sense of the atmosphere of Rembrandt’s pupil’s atelier in this remarkable period, charged with verve, ambition, and new pictorial ideas.

The painting hanging in The Wallace Collection shows four figures in an interior, arranged frieze-like across the foreground. Although it has also been interpreted as The Parable of the Unmerciful Servant, it clearly depicts the story told in the book of Acts, of the Roman Centurion of the Italian Legion stationed in Caesarea.4 A devout man, he receives a vision instructing him to call for Simon Peter, the lead disciple of Jesus. According to the text he sends three men: two servants and a soldier, as we see here. His subsequent meeting with Peter will result in him becoming the first Gentile convert to Christianity. Here he takes a commanding pose to the left of centre, wearing not the armour of a Roman commander, but instead Oriental dress consisting of rich robes and a fantastic turban. This choice was perhaps even directed by Rembrandt: it also appears in a painting of the same theme by fellow Rembrandt pupil Barent Fabritius (fig. 2).5 The artist’s reasoning likely saw the Centurion in his domestic sphere, free to wear local dress. His costume refers to the region in the Centurion’s charge, but perhaps also, even more significantly, to the Eastern religion to which he adheres, which at this point is still limited to Jews. His outstretched arm clearly communicates a dispatch, to the three men standing across from him in an obliquely receding row. The rightmost is a soldier wearing a heavy helmet and a gorget over a simple grey smock. A sword with curved handle hangs from the red embroidered sash around his waist. Off to the left stands an older man with grey beard and hair and ruddy features, and like the soldier he looks earnestly across to the man in the turban. The Centurion in turn directs his gaze to the middle man of the three, who wears a loose white shirt and a yellow coat with red leather strips. Holding his fur-trimmed cap between his hands, he leans forward, listening attentively. He will be the one to deliver the message that will open Christianity to the Gentile world.

This impressive work long passed as a Rembrandt. This attribution was only first questioned in 1923, not surprisingly by the contrarian John C. van Dyke.6 In 1929 he was seconded by Abraham Bredius, who proposed Willem Drost instead.7 In 1979 it became one of many shaky attributions by Henry Adams to Karel van der Pluym, Rembrandt’s second cousin who studied with him in the late 1640s. Van der Pluym mainly imitated the small-figured mode Rembrandt applied in these years. Although he did try out a larger figure scale in later works, he adhered to the layered application of translucent paint already evident in his early works. His compositions are marked by a rhythmic pattern of accents yielding a pleasant patchy clutter, giving his works a disarming charm, quite removed from the boldness and monumentality of The Centurion Cornelius.

That painting nonetheless did originate in Rembrandt’s workshop, as established by technical evidence. In her survey of the grounds of paintings by Rembrandt and his circle, Karin Groen indicated the presence of quartz in the preparatory layers of this painting.8 Wider research has further confirmed her hypothesis that this ingredient uniquely characterizes the products of Rembrandt’s workshop, by his hand and also by his pupils.9

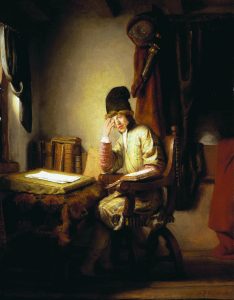

The Centurion Cornelius relates to a period in Rembrandt’s stylistic development that falls decidedly after Van der Pluym’s stay. It follows the new artistic path that Rembrandt set around 1651. With restrained dynamism in poses and painterly open brush work, he began exploring the quiet evocation of inner emotion and experience. Through isolation of the main figures, often using a larger, monumental figure scale, and accentuating with striking side lighting, he achieved greater concentration on the evocation of inner state of the figure. It was a decisive transition from the virtuoso display of artistic principles and effects in small-figured compositions of the 1640s. The opening volley appears to have been the Kitchen Maid of 1651 in Stockholm,10 and an early, grand masterpiece is his Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, of 1653, which may have been the source for the Centurion’s pose and appearance (fig. 4). Rembrandt evidently dragged his pupils along with his new “research”. Drost was one of the first pupils to take the new mode with him as he launched his independent practice in 1653; he may well have seen the Aristotle, as well as The Centurion Cornelius, started before leaving.11

It was another pupil who painted it. In rejecting the attribution to Drost in his dissertation and subsequent monograph on him, Jonathan Bikker observes that it does not achieve the strong sense of form that was one of Drost’s great strengths developed under Rembrandt’s tutelage. The theoretical term houding was used to describe this effect, of which Rembrandt was recognized in his time as the undisputed master.12 But The Centurion Cornelius follows Rembrandt into the new and uncharted territory of the 1650s. Most striking is the bold application of paint in various places. A singularly accomplished and daring passage of brush work appears in the white shirt of the younger servant. Also deserving mention are the red straps hanging from the fringe of his coat, more thinly brushed. Direct strokes of thick and opaque paint surface in other areas as well, as do strong colour combinations. For judging the individual artistic hand at work, the Centurion’s face is especially significant, owing to its striking juxtapositions of reddish and yellowish hues that achieve a kind of flat surface pattern. This daring painterly experiment goes beyond anything seen in Rembrandt’s work or that of other pupils, and the young artist responsible clearly wanted to give an imposing presence to a mature visage, complete with wrinkles and folds. The old servant shows similar handling, whereas the young soldier and servant are more smoothly and conventionally modelled.

Clearly, we are witnessing the work of a particularly enthusiastic pupil, applying but not yet mastering all of the elements in play in Rembrandt’s tutelage at this moment in his development. He did not sign his name, but did leave an extremely telling trace of his hand behind, an undisguised weakness, in the right sleeve of the Centurion. The drapery there ceases to make sense, the folds conjuring abstract shapes instead of a logical fall of fabric. It is very notable that a similar “nonsense” drapery passage appears in the left sleeve of a single-figure depiction of Mars in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a work that has already been linked to this painting (fig. 5).13 Jonathan Bikker points out that the same helmet appears in both, with a plain clamshell top and a row of golden rosettes around the base.14 Additional evidence surfaces in its ground layer of the Mars, whose composition, including quartz, is nearly the same as the Centurion.15 The Mars has been attributed to various Rembrandt pupils, including Heyman Dullaert, whose study period does align with the time period in question, around 1652-1653. In 2015, the author first proposed an attribution of The Centurion Cornelius to Dullaert as well, in a footnote in the catalogue to the Rembrandt House exhibition on Rembrandt’s late pupils.16 He pointed to the abovementioned drapery quirk as a tell-tale trait, but there is more. Research yields further links, and a new attribution to this overlooked pupil, who occupied a distinctive place in the atelier.

Heyman Dullaert, a pupil from Rotterdam

Arnold Houbraken wrote with special enthusiasm about Dullaert in his Great Theatre. He perceived in him a kindred spirit, devoted not only to painting, but also to poetry.17 Dullaert is indeed known for a body of competent verse that, as Houbraken claims, places him among the higher ranks of contemporary Dutch poets. But Houbraken also asserts his achievements with the brush, in particular as a pupil in Rembrandt’s workshop. Well known at the time was a depiction of Mars in which Dullaert successfully rendered the god’s shining armour.18 Art historians have long danced around the tantalizing prospect that the Mars in the Metropolitan could be this very work.19 Houbraken tells that, according to the husband of the artist’s niece, this painting was sold “as a genuine work by Rembrandt, in Amsterdam”. This seems hard to believe of the Metropolitan Museum painting, according to our standards, but the mix of family legend and shop terminology could well be in play here, however, pertaining to a finished pupil’s work that was allowed to do out the door as a Rembrandt Workshop piece, not necessarily as a “principael” or original work by the master. Such a workshop piece would have marked the pupil’s complete competence as a “discipel”, an advanced pupil who had successfully adopted the master’s style, even if it was not at the master’s level of art.

Dullaert was born in Rotterdam, the eldest son of the grain dealer Kornelis Dullaert, from a prominent regent family in the city.20 The family attended the Walloon Reformed Church, and Heyman received a solid education, probably finishing with the city’s French schoolmaster Philip de Rieu, while developing his talents as singer and musician at the same time.21 Probably around 1652, he entered Rembrandt’s pupils atelier as a disciple.22 Besides the accounts of Houbraken and David van Hoogstraten, his presence there is attested to by his signature as a witness to a notarial document of 1653 in which Rembrandt empowered Françoys de Coster to collect debts on his behalf.23 He probably stayed on for two years, returning to Rotterdam in 1656, where his translation of a bundle of sermons was published the following year by François van Hoogstraten, a literary brother of Samuel van Hoogstraten who had just moved to the city. In 1658 he contributed a poem to a pietistic volume on the Lord’s Prayer published in Amsterdam, joining Rembrandt’s good friend Jeremias de Decker, and Hendrik Frederik Waterloos, whom he likely also got to know from his time in the studio.24 Although he likely continued to paint, writing came to dominate his output, and certainly his circle of contacts. Nonetheless, he also developed a bond with Philips Koninck, who painted a remarkably moving and original portrait of him, likely around the time he left the studio (fig. 6). Koninck can be counted with Roeland Roghman and Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, as one of Rembrandt’s friends. Houbraken plausibly claims that Dullaert also developed close ties with his teacher.25 Jacob Campo Weyerman even referred to written correspondence with Rembrandt and Koninck,26 but this is likely one of his frequent embellishments of Houbraken. While Dullaert and Van den Eeckhout did publish poems,27 no traces of any written exchange with Rembrandt or Koninck survive, and furthermore we do not know Rembrandt to have written any more letters than necessary.

Dullaert also looked across the pupil’s atelier to the work of his companions at the time. In his painting of a Uroscopist, now in the museum in Groningen (fig. 7), he adapted the concept and composition of Willem Drost’s painting of A Young Man in his Study, now in Copenhagen, as Sumowski already observed.28 Drost in turn had derived his composition from Rembrandt’s printed Portrait of Jan Six of 1647,29 and from a preparatory drawing for it.30 The distinctive feature of an alcove with a bedstead to the right was Drost’s own addition, and Dullaert took this over in his composition. Dullaert recognized the significance of this feature for Drost’s demonstration of houding, the convincing and engaging evocation of spatial relationships, and he likewise attended to this element in his own painting. This was part of instruction of course, and Drost may have even served as a head pupil in the studio, with teaching duties. Dullaert evidently cherished the memory of Drost, who had gone on to Venice and died there suddenly in 1659.31

It was already a distant memory by then. Dullaert did not make his painting during his period in the studio, at Drost’s side. Instead, the smooth handling of surfaces and colourful palette reflect later trends in genre painting, for example the paintings of fellow Rotterdam artist Ludolf de Jongh (1616-1697). This was likely sometime around 1660, a time when other Rembrandt pupils in nearby Dordrecht (Nicolaes Maes, Jacobus Leveck and Abraham van Dijck) also adopted newer fashions in art and moved away from their teacher’s model.32

In 1983, Werner Sumowski noted the link between the Groningen Uroscopist and a painting of A Young Scholar in his Study in the Bader Collection (fig. 8).33 He pointed to the similarity between the coat the young man wears and the one the doctor has lying on the floor behind the chair. The chair is of course also very close, while the setting and motif are more loosely related. However, the style of The Young Scholar is closer to Rembrandt than The Uroscopist: the palette is dominated by warm brownish hues and the handling features open brush work and layering of translucent layers to suggest various surfaces and textures. The effect of light and shade is also much stronger. The Kingston painting must date to only a few years after the period of study.

The Kingston Scholar also relates in turn to The Centurion Cornelius. Emerging from the student’s rich oriental striped robe are lavish silk sleeves, dyed in a highly conspicuous salmon pink colour, with pinking and slashes in bands. Nearly exactly the same textile (reflecting fashion around 1600) adorns the arm of the Centurion in London. The artist must have had access to a piece of this such fabric, likely part of the generous collection kept in Rembrandt’s pupil’s atelier,34 and gave it the same role in both works, as a decorative highlight underscoring a telling gesture: the Centurion firmly planting his hand as he issues a command, and the weary student fighting sleep by rubbing his eyes.

On its own this element might not show more than a piece of fabric rendered in two different works, and does not exclude the possibility it was shared between artists. However, another equally conspicuous element links these works, and the Mars in New York as well. The curving folds in the sleeve of the student’s coat form a “nonsense” pattern, defying gravity, fully consonant with the Centurion’s sleeve. The same applies to the student’s other sleeve, with stiff and artificial lateral arcs in the fabric. There is a strangely unnatural fold in the brown drapery in front of the bed behind him as well, above the arm and a bit to the right. In the painting of Mars in New York, the rich red fabric on the god’s raised arm blasts beyond nonsense and on through to crazy. Dullaert was clearly used to rendering the fall of fabric folds from imagination, and not from life. Specific weaknesses like this are rarely feigned or transferred in copying, and can thus function like an unintended signature.

We have one further painting that appears to originate in Dullaert’s period in Rembrandt’s pupil’s studio: a large depiction of Jacob Receiving Joseph’s Bloody Coat in the Hermitage.35 We should only consider the central portion, from before this work was greatly enlarged on all four sides around 1781. The stylistic link to The Centurion Cornelius is already evident in the striking light, the monumental presentation of the figures in a frieze-like arrangement, and more specifically in the bold, almost erratic handling of paint, including similarly jarring direct strokes of yellow in Jacob’s coat. One key element is less obvious, however: peeking out from the sleeve of Joseph’s mantle is a short length of the sleeve of his jacket, of pink silk, with the same slashes and pinking as in the Centurion’s prominent sleeve. We can also find various traces of Dullaert’s “nonsense” drapery folds, unobserved and unconvincing, especially in the bloody coat, and in the cloth of Jacob’s coat that rests on his lap (fig. 9). These many similarities allow us to consider an attribution of the Hermitage painting to Dullaert as well.

|

|

|

|

One of Dullaert’s signed works supplies a significant parallel to his curious recklessness with drapery: the Still Life with Tropical Fruits, Bread, and Drinking Vessels in Jerusalem (fig. 11). Here he concentrates on bold presentation of the objects with strong contrasts and direct strokes of paint, as in the Centurion. Detail is not a priority, but neither also is accuracy in rendering of forms. The distinctive diamond grid pattern of the glass decanter in the right foreground is curiously skewed, especially the bright yellow highlight just to the lower right of centre, laid in with a thick impasto strokes of opaque colour. It looks like the young “discipel”, now independent and signing his own name, is still caught up in the excitement of the bold painterly handling that Rembrandt is developing, and teaching in the first half of the 1650s, and applies it to very different subject matter rarely treated there.

A parallel also emerges with the Mars in the Metropolitan Museum. His armour is rendered brilliantly in bold strokes of paint and strong contrasts. In the same way, the still life arrangement of books, paper and ink well in The Centurion Cornelius is rendered in brilliant light, with solid strokes of thick colour. This can be no coincidence. The combination of masterful still life detail, with less assured treatment of facial features and drapery folds forms a conspicuous match with the student in Kingston as well. Dullaert’s talent in still life is already known from depiction of a letter rack now in Otterlo, complete with calligraphically inscribed signature on a letter, and a 1632 book of regulations pertaining to grain dealing, his father’s trade (fig. 12). The bright metallic reflections in the keys to the upper right reveal its links to the Jerusalem still life, as well as to the Centurion Cornelius and Mars. There are various direct strokes of colour, characteristic for his youthful, Rembrandtesque phase. At the same time, the softer modulations of tone suggest a later date. Dullaert most likely took his cue from the literary trompe l’œil letterboard still lifes that Samuel van Hoogstraten started to produce in Dordrecht around 1656.36

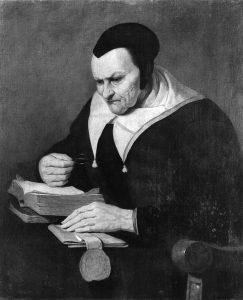

Still life became a forté of this Rembrandt pupil. An arrangement of books and a large seal appears prominently in a painting of An Old Woman with Books last in a private collection in Brussels (fig. 13).37 She is shown pausing in serious reflection from her study, following a pious type based on Rembrandt models seen in the workshop and cultivated further in Dordrecht by fellow pupil Abraham van Dijck (1635-1680). A reproductive drawing by Jan Stolker after a copy of this painting includes an inscription in the stone window frame embellishment, attributing the painting to Dullaert and identifying the woman as his mother, “Sophia”(sic) Melisdijk, aged 80.38 The attribution looks to be correct, and the same seal with the Lion of Holland reappears in the signed still life in Otterlo (fig. 12). However, the identification of the figure was clearly fudged: Dullaert’s mother never reached an old age, but instead died young, in childbirth.39 The costume is everyday dress, not formal, confirming that this is not a portrait but a genre scene.40 Remarkable is the inclusion of the parchment document with the seal, most likely a charter relating to ownership of land. In a scene of an old person piously contemplating the Bible and its promise for the hereafter, Dullaert appears to have incorporated a creative reference to Jesus’ admonition in Matthew 6:19-21: “Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys, and where thieves do not break in or steal; for where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” The woman appears to hold the document under her left hand, which suggests a rejection of its importance. She instead favours the book she is reading: it appears to be a Bible.

This painting also reflects Dullaert’s later style. Judging by the available black-and-white photographs, it shows a smoother overall paint handing with no open brush work. This contrasts with Rembrandt’s manner of building up layers with open brush work, which was highly suited to evoking the translucency and wrinkles of aging skin. The stylistic shift undertaken around 1660 by fellow pupils of the 1650s such as Nicolaes Maes favored smoother surfaces, less visible brush strokes, and more opaque colours yielding a flat surface effect. Dullaert evidently followed suit. The hands and face of the woman show smooth patches of opaque colour over a darker underground, with a dark underlayer showing in the spaces between indicated creases and wrinkles, to harsh effect. A date of around 1664 seems likely: the distinctive cap with flaps at the ears and a peak over the forehead surfaces in a few genre depictions by Quiringh van Brekelenkam between 1661 and 1664, in combination with the collar with the long tips hung with tassels.41

Dullaert’s signed Uroscopist shows a similarly smooth handling and use of opaque colour, suggesting a similar date. Direct and open brush strokes do not factor here anymore, and the evocation of space depends entirely on light, contrasts, and colour. Nonetheless, Dullaert here still professes his link with the Rembrandt studio and his presence there in the company of Drost, as discussed above. The function of the Uroscopist as a reminiscence lies not just in the composition however, but also in a reference that has hitherto escaped notice, in the open page of the book on the table (fig 14). The illustration shows a simple composition, with one man on the left and two on the right. A single pen stroke beside the rightmost figure is enough to indicate that he is armed with a sword, just like his counterpart in The Centurion Cornelius. The composition is more tightly cropped, and aligns more closely with a drawing in the Rijksmuseum that has always been seen as preparatory to the Wallace Collection painting (fig. 15). Peter Schatborn sees the drawing as a copy of a lost sheet by Drost, and although Jonathan Bikker questions this complex scenario, it nonetheless appears likely, or the sheet could even be original.42 Dullaert likely recalled Drost’s drawing, much as he did Drost’s painting now in Copenhagen. His Uroscopist evidently incorporates multiple references back to his glory days in Rembrandt’s studio, around ten years after he painted his single most striking work there, The Centurion Cornelius.

We are left with a moving image of an enthusiastic, agreeable, but frail Heyman Dullaert, boldly and daringly painting a large canvas in Rembrandt’s pupils’ atelier around 1653. The Centurion Cornelius shows this discipel caught up in the excitement of the master’s new turn towards psychological concentration and direct brush work. He was evidently stoked further by his older fellow pupil Willem Drost, the most gifted interpreter of the new mode, likely filling the influential role of head pupil. Dullaert’s deeply Rembrandtesque work went unrecognized for centuries, because he did not continue in this vein, but shifted to other subject matter, and left his signature mainly on genre and trompe l’œil paintings.43 Now identified, The Centurion Cornelius exits the company of works that long languished in anonymity.

About the author:

From 2001 to 2014 David de Witt was Bader Curator of European Art at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, where he published two catalogues of the Bader Collection (2008 and 2014), before moving to The Rembrandt House Museum, where he is Senior Curator, contributing regularly to exhibitions and catalogues, most recently Rembrandt’s Social Network (2019) and HERE. Black in Rembrandt’s Time (2020). Besides monographs on Jan van Noordt (2007) and Abraham van Dijck (2020), he has published articles on Jan Lievens, Abraham van den Tempel, Jacobus Leveck, and of course Rembrandt. See also: https://www.codart.nl/guide/curators/dr-david-de-witt/

- After Pieter Lastman, Susanna and the Elders c. 1636, red chalk, brush in grey by another hand, 235 x 363 cm, Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, inv. no. KdZ 5296; Peter Schatborn, in: Peter Schatborn and Erik Hinterding, Rembrandt. The Complete Drawings and Etchings, Cologne 2019, p. 440, no. D661.

- See Jonathan Bikker, Willem Drost: A Rembrandt Pupil in Amsterdam and Venice, New Haven and London 2005, p. 135, no. R5.

- This painting has often been connected with one cited in the inventory of Hillebrand van der Walle in Delft drawn up on 1 February 1672. See: John Ingamells, The Wallace Collection. Catalogue of Pictures, London, IV, Dutch and Flemish, London 1992, pp. 89-95, and most recently Jaap van der Veen in: Rembrandt’s Late Pupils: studying under a genius, Amsterdam: The Rembrandt House Museum, 2015, p. 28. However the Centurion there is explicitly described as seated, which is very clearly not the case here.

- It first appeared as such in a sale of 1848, although already identified previously as The Centurion Cornelius. See Bikker 2005 (see note 2), p. 135, sub. no. R5.

- Werner Sumowski, Gemälde der Rembrandtschüler, 6 vols., Landau 1983-1994, II (1984), p. 918, no. 559 (ill.).

- John C. van Dyke, Rembrandt and his school, New York 1923, p. 175.

- Abraham Bredius, “Rembrandt of Drost?”, Oud Holland 46 (1929), p. 41.

- Karin Groen, “Tables of Grounds in Rembrandt’s Workshop and in Paintings by his Contemporaries”, in: Ernst van de Wetering et al., A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, vol. 4, The Hague 2004, p. 664: “quartz, clay minerals, ilmenite, a little umber, red ochre, a little chalk”.

- Michiel Franken, “`Dat alles op die leest moest geschoeid wezen’. Over navolging in de schilderijenproductie in Rembrandts werkplaats”, in: J. Rutgers and M. Rijders, eds., Rembrandt in perspectief. De veranderende visie op de meester, Zwolle 2014, pp. 83-84.

- See also Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt’s Paintings Revisited. A Complete Survey. A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, Dordrecht 2014, p. 340.

- See Bikker 2005 (note 3), p. 11.

- Paul Taylor, “The Concept of Houding in Dutch Art Theory”, Journal of Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 55 (1992). p. 227.

- Walter Liedtke, Dutch Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2007, I, p. 730.

- Bikker 2005 (see note 2), pp. 137-138.

- Groen 2004 (see note 6), p. 664: “quartz, clay minerals, ilmenite, brown ochre, a little red ochre, chalk”.

- David de Witt, in exh. cat. Amsterdam 2015 (see note 2), p. 116, note 9.

- Arnold Houbraken, De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen, Amsterdam, vol. 3 (1721), pp. 79-80.

- Ibidem.

- Liedtke 2007 (see note 13), p. 727.

- P.C.A. van Putte, Heijmen Dullaert, Groningen 1978, I, pp. 5-6.

- Ibidem, p. 17.

- Ibidem, p. 17.

- http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl/#/document/remdoc/e4637

- ’t Gebedt onzes Heerens, Amsterdam: 1658.

- Arnold Houbraken, De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen. Dordrecht 1719-1721, III (1721), p. 79.

- Jacob Campo Weyerman, De levens-beschryvingen der Nederlandsche konst-schilders en konst-schilderessen. II, The Hague 1729, p. 390. My thanks to Michiel Roscam Abbing for this reference.

- Van den Eeckhout mainly wrote poems on fellow artists and their works, including one on a drawing of an ice scene that Jan van de Cappelle (also a friend of Rembrandt) had contributed to the Album Amicorum of Jacobus Heyblocq; see: Kees Thomassen and J. A. Gruys, eds., The Album Amicorum of Jacob Heyblocq: Introduction, Transcriptions, Paraphrases, and Notes to the Facsimile, Zwolle 1998, pp. 173–174.

- Sumowski 1983-1994 (see note 4), I (1983), p. 653, no. 343.

- Ibidem, p. 613, no. 318.

- Amsterdam 2015 (see note 3), p. 89.

- Bikker 2005 (see note 2), p. 40.

- On Van Dijck see David de Witt, Abraham van Dijck c. 1635-1680: Life and Work of a Late Rembrandt Pupil. Zwolle 2020.

- David de Witt, The Bader Collection: Dutch and Flemish Paintings. Kingston 2008, pp. 114-115, no. 65 (ill.).

- http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl/#/document/remdoc/e12729

- Sumowski 1983-1994 (see note 5, IV (1989),p. 2950, no. 1938 (ill., as Unknown Artist).

- For example: Letterboard Still life with the manuscript of Eerlyken iongeling, c. 1656-1657, canvas, 53.5 x 69.5 cm, France, private collection; see Michiel Roscam Abbing, De schilder & schrijver Samuel van Hoogstraten 1627-1678: Eigentijdse bronnen & œuvre van gesigneerde schilderijen, Leiden 1993, p. 117, no. 18 (ill.).

- Sumowski 1983-1994 (see note 5), vol. 1 (1983), p. 654, no. 348, p. 660 (ill.).

- Sturlla Gudlaugsson, “Een teruggevonden werk van Heiman Dullaert”, Kunsthistorische Mededelingen 4 (1949), pp. 41-44, where the drawing is given as in the Rijksmuseum, which later turned out not to be the case: the sheet is untraced. See Robert Jan te Rijdt, “Een ‘nieuw’ portret van een ‘nieuwe’ verzamelaar van kunst en naturaliën: Jan Snellen geportretteerd door Aert Schouman in 1746”, Oud Holland 111 (1997), p. 33 (fig. 10, as Portrait of Fijtgen Heymansdr. van Melisdyck).

- Van Putte 1978 (see note 20), p. 13.

- My thanks to Marieke de Winkel for her kind and valuable assistance with the identification and interpretation of the costume for this and other paintings in this article.

- For example, A Mother Feeding a Child, monogrammed and dated 1661, oil on panel, 30.5 x 25.5 cm (oval), Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. SK-C-113;and: A Tailor’s Workshop, signed and dated 1664, panel, 49 x 38 cm, present location unknown (London, Bennett Gallery, in 1958); see Angelika Lasius, Quiringh van Brekelenkam, Doornspijk 1992, p. 97, no. 57 (ill.), p. 120, no. 142 (ill.).

- Schatborn cited in: Werner Sumowski, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, III, New York 1980 (1980), p. 1236, no. 567xx. Bikker 2005 (see note 2), p. 138.

- Dullaert’s signature appears on one history painting, a depiction of Cimon and Iphigenia in the museum in Épinal, in a very smooth and colourful manner, influenced by Caspar Netscher, indicating a date after 1670; see Sumowski 1994 (see note 5), p. 651, no. 344.